THE DAILY CHORE

THE DAILY CHOREby Larry Brundage

(Webmaster's note: This article was scanned from the Fall 1997 issue of ToolTalk.)

By a fortuitous turn of events, PAST Member Dave Paling obtained the discarded relics and dreams of Pierre Basmaison, a carpenter, inventor, and resident of San Francisco. Basmaison lived in the City from 1902 until his death in 1955.

Basmaison was born in 1863 in Thiers, Puy DeDome, France. He immigrated to America in 1900. By 1910 he was living at 1234 Diamond Street, in the Noe Valley section of San Francisco, with his wife Emilie, son Lucien and daughter Marie.

This was to be the only home the entire family ever lived in, as neither of the children ever married The children lived at the home place for the rest of their lives, with Lucien being the last resident, passing away in 1984.

DUMPSTER FIND

Some time after Lucien's death, the house was cleaned out. Amongst the debris was Basmaison's large accumulation of decayed correspondence and rusty tools that spanned the years of his efforts toward making the life of his fellow carpenters easier.

While going through a dumpster, an antiques picker found this accumulation, which was eventually purchased by Dave Paling and later passed on to me through AI Bennett.

While there were numerous letters pertaining to his various patents, no papers were included to shed a light on the man behind the tools. What I gleaned about Pierre Basmaison came from his patent correspondence and the various tools that I found in the accumulation.

THE DAILY CHORE

THE DAILY CHORE

Pierre Baismaison disliked sharpening plane irons. In the early years of this century, he tinkered to find ways to avoid the chore that wood- workers have to perform daily. Basmaison was granted four patents that went from complicated to not quite as complicated. I say this from a manufacturing and users' viewpoint. The basic idea was to not sharpen the edge, but to replace it with an inserted blade. THE. PROTOTYPE. STAGE

His first version would have required finicky machining and metal bending plus a blade with a right angle on it. This plane iron would have been hard to form. When you had to replace it, your chances of getting nicked would have been high. This version was issued on Feb. 26,1924 (Patent No. 1,484,861).

His next version was issued on June 10, 1924 (Patent No. 1,497,474). It was even harder to understand as the device had bends, rivets and screws, with tricky spring copper to bend and install.

In the available correspondence, there is no evidence that these plane irons were ever manufactured beyond the prototype stage, as only a few samples were in the box of rusty tools.

Basmaison fired off many letters to patent people in New York City and Ottawa, Canada and obtained favorable letters from two Carpenters Unions (Nos. 22 and 483) in San Francisco, but no purchase orders ensued and the return letters from the people he asked to help him sell his patents had no encouragement.

BACK TO THE DRAWING BOARD

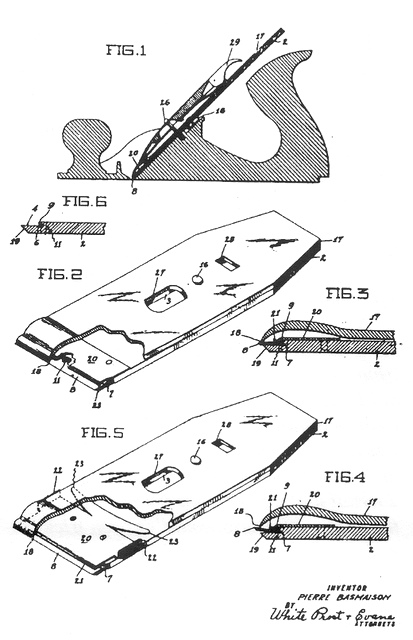

Basmaison was not deterred. He went back to the drawing board, and after much experimental machining and suggestions from the machinist, he came up with Patent No. 1,574,725, issued on Feb. 23,1926.

This version went into production because a damaged photo survived that shows the bottom part of the plane iron setup in a milling machine. The cutter is milling out a beveled groove that holds the thin replaceable blade firmly in place.

Another photo shows a different view of the shop. From a business card found

in the mass of paper, it might be the I.F. Pagendarm, Binns Machine and Tool

Works located at 71 Perry Street in San Francisco, circa 1922-26.

Another photo shows a different view of the shop. From a business card found

in the mass of paper, it might be the I.F. Pagendarm, Binns Machine and Tool

Works located at 71 Perry Street in San Francisco, circa 1922-26.

This shop probably also manufactured the 2 inch by 1/4 inch inserted blade. In the box of tools, there was a large quantity of finished and unsharpened blades, plus a mass of labels for the small box that held 5 of them. Only one cardboard blade box survived. I found only small bits of cardboard in the tin box that held the loose blades and gummed-together labels (see box below).

-I wish I had been able to rummage through the mass of debris that was

thrown in the dumpster, and salvage every scrap of paper that Basmaison had

saved. If any of you reading this have additional information on this subject,

please write or call:

-I wish I had been able to rummage through the mass of debris that was

thrown in the dumpster, and salvage every scrap of paper that Basmaison had

saved. If any of you reading this have additional information on this subject,

please write or call:

Larry Brundage

510 Cleveland St.

Redwood City, CA 94061

415-368-5512

P. Basmaison Bit

Patent No. 1,574,725

Patent Date: Feb. 23, 1926

In the box of parts, this model was plentiful. Figure 6 shows the milled part of the base iron. Figures 3 and 4 show the bit (number 7) in place. Figure 2 shows number 11, a pin 3/32 in diameter which engages the bit and prevents it from moving sideways.

The back edge of the bit is held firmly in place by a formed copper spring, about .020" in thickness. It has right angle tabs (number 22 plus number 23) and two pressure wings which are bent up and pushed against the cap iron. This ensures that the bit cannot shift. The top of the cap and base iron are marked as such:

US. PATS

2-26-24

6-10-24

2-23-26

Among the mass of Pierre Basmaison 's papers were two sets of patent papers that pertained to inserted plane blades.

The earliest was awarded to Newton D. Merwin on June 12, 1922 (Patent No. 1,419,400), and the other to Thomas T. Tvedt on January 2, 1923 (Patent No. 1,440,649).

Evidently Basmaison wisely checked to see if his ideas infringed on other patents. Although in a kindred spirit, the mechanics of his ideas differed in blade design and basic mounting features. Like Basmaison's, the design of Merwin's insertable blade involved machining a small dovetail in the base plane iron, which held the blade. This also would've been tricky to make accurately in volume and to sell cheaply.

Stanley Ready Edge Blades

On examining Thomas Tvedt's patent, I was struck by its similarity to the Ready Edge Blades, patented by Stanley and made by them from about 1925-29.

They differ in that Tvedt used a double edge blade which was held in place by two pins. When one edge was dull, you just turned the blade around.

Whereas the Stanley blade was single edged and installed from the front. It was held in place by two slotted pins, which probably had threads and could be replaced easily if damaged.

I doubt if anybody made any real money from this novel feature, as examples are scarce. We know for sure you won't find many of them at a tool sale.

-Larry Brundage